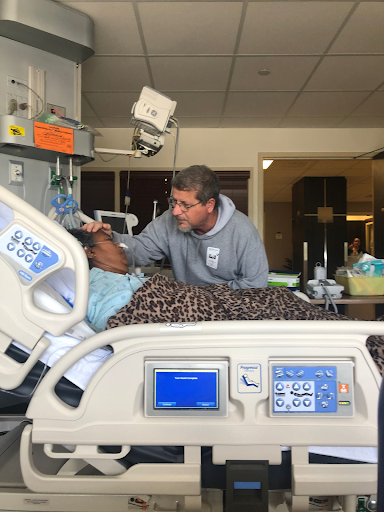

During the last seven years of my wife Maggie’s life, she suffered from neurosarcoidosis, a chronic autoimmune disease in which the body’s immune system attacks the central nervous system. Each episode of inflammation caused irreparable damage to her ability to function independently. The drugs she took to manage the neurosarcoidosis caused Type 2 diabetes, weight gain, water retention, diabetic peripheral neuropathy and electrolyte imbalance. They also suppressed her immune system and affected her kidneys and liver. Her doctors prescribed drugs to manage the side effects. Maggie also suffered from cardiovascular disease (she had four strokes in less than a year) and pulmonary hypertension, all of which required more drugs. The neurosarcoidosis robbed her of memory, her ability to converse, her ability to work and to drive, and sometimes of time and reality. The strokes sapped her strength and her balance. By the end of her life, she was taking three drugs for neurosarcoidosis, two for blood pressure, three anticoagulants, four for diabetes, one for acid reflux, two for cholesterol and one for water retention. Still, with all the medical burdens Maggie bore, with all the indignities she suffered while being poked and prodded and X-rayed and MRIed and CAT-scanned, what she couldn’t abide was her loss of independence. This wasn’t simply — or merely — losing the ability to jump in the car on a whim and meet friends for lunch.She had behind her a lifetime as a vibrant, inquisitive, gregarious human being; of helping others as a political activist, an ASL interpreter and a social worker; of taking care of friends and family. I think she felt the circle of her world tighten around her as the radius of her independence decreased. She spent more and more time in her recliner, which seemed to become the centre of that circle.

Full Story